Most Oregon school boards will formally adopt 2024-25 budgets in June, but the real decisions are being made now as boards digest some disheartening numbers.

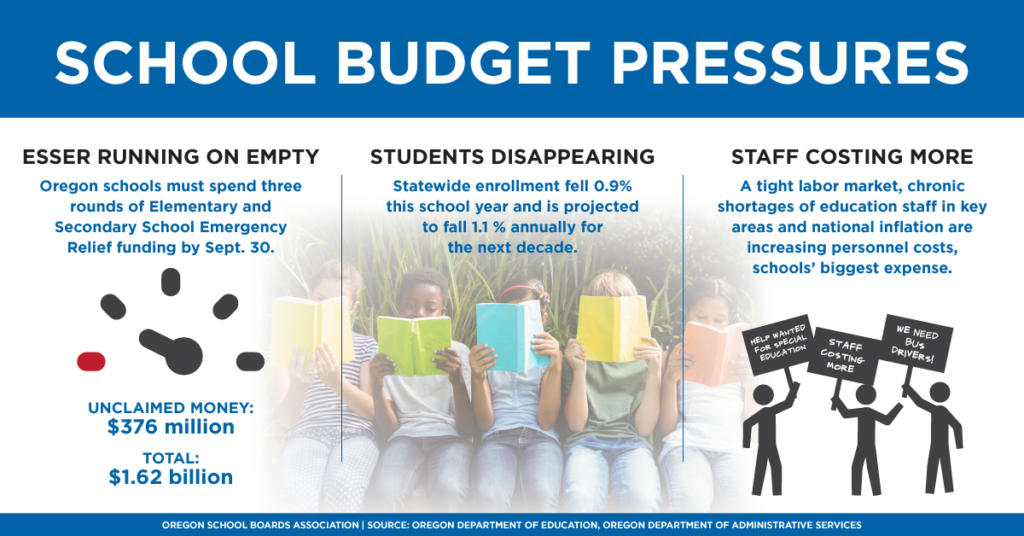

Just as school leaders and business officials warned, the $10.2 billion 2023-25 State School Fund isn’t enough for all districts to maintain their current staffing and programs. Three additional forces are making this the most difficult budget season in years for some: falling enrollment, soaring staff costs and the loss of federal emergency funding.

“Some are going to be hurting,” said Jackie Olsen, executive director of the Oregon Association of School Business Officials. “Some are not.”

The wide disparity lays bare some of the inadequacies and inequities of Oregon’s public school funding approach. Districts are in wildly varying positions often because of factors out of their control, including costs associated with their location, student population demographics and local tax support.

Education advocates and state leaders are working now on legislation to reform Oregon’s school funding approach during the 2025 legislative session. They are focused on funding and accountability, the heart of budgeting.

School board budget committees are grappling with the realities of a State School Fund formula that doesn’t take into account schools’ many annually shifting costs.

“It’s not an accurate calculation anymore,” said Tigard-Tualatin Board Chair Tristan Irvin. “You can never get ahead if that is the calculation being used.”

Tigard-Tualatin is working on its second cuts budget in a row. Irvin, an OSBA Board member, is clear on the root cause: “More needs and less money.”

Districts are spending more per student to cope with the ongoing behavioral and academic fallout from the pandemic. But Tigard-Tualatin’s funding is dropping because it is losing enrollment.

Oregon school funding is tied to enrollment. It’s not a straight head count, though. The “average daily membership weighted” gives extra money for students in specified categories that require additional education resources. Legislators have proposed changing the ADMw formula, but education advocates are wary of any change that shifts money around without adding to the total.

Public school enrollment dropped dramatically when schools shifted to online learning during the pandemic. District leaders say their ongoing enrollment drops, though, are more attributable to declining state birth rates and local housing and demographic trends. Oregon economists predict public school enrollment will continue to fall into the foreseeable future.

Total Oregon enrollment was down 0.9% for 2023-24, raising slightly the per-student allocation for this year. That enrollment loss is not spread evenly though. Districts that lost more than the state average will end up with a net loss.

The La Grande School District is almost 300 students below its pre-pandemic enrollment after falling 3.2% this year. Superintendent George Mendoza estimates that’s about a $700,000 hit to the budget.

La Grande got an extra kick in the teeth with its ADMw. The federal census lowered the district’s number of students in poverty, meaning the district will lose about $330,000 in funding.

Staffing, more than 80% of most districts’ costs, bears the brunt when districts must cut. Soaring inflation and a tight labor market, though, put districts in a weak bargaining position for limiting raises, increasing class sizes or reducing support staff.

The 2023-25 State School Fund did districts no favors. Legislative analysts predicted compensation would increase 5.45% in 2023-25 when setting the funding level. Districts around the state are reporting significantly higher contract demands, with Portland Public Schools, where teachers went on strike, and Salem-Keizer Public Schools, which narrowly avoided a strike, the most obvious examples.

La Grande’s teachers have asked for more too, Mendoza said.

La Grande has budgeted for a $750,000 increase in staffing costs, although negotiations are still going on. The 2023-25 fund was close to what La Grande needed to maintain its current staff and programs, but “close doesn’t get you to the next negotiation,” Mendoza said.

“Inflation happens, contracts end, and people want to be paid a fair market wage and you have to have new money to do that,” he said.

Education advocates and legislators this year are also exploring how to better manage school staffing costs and reflect them in the State School Fund.

The winding down of the federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding has complicated the calculus. ESSER pumped up school budgets during the pandemic, and financial experts left and right yelled, “Don’t spend it on personnel!”

School leaders knew spending one-time money on staff costs risked layoffs when the money ran out, but students needed more support and pay bumps helped retain existing staff. Some districts hired staff and started programs with the idea that if they were successful, there might be more money down the road or they could cut something else to make room.

Oregon is down the road, but more money isn’t there. Budget committees this month will hear about ESSER-related cuts.

ESSER allocated $1.6 billion to Oregon, and the last of that money (with some exceptions) has to be committed by Sept. 30. Oregon has spent most of it already.

Tigard-Tualatin put ESSER money into staff and programs where it would impact students directly, Chief Financial Officer David Moore said. Tigard-Tualatin will have spent all its ESSER money by the end of this budget year, according to Moore, leaving the district with about $4 million in unsupported costs.

“We will have to quit what we are doing with those dollars or find other funds in our budget,” Moore said.

Those will be hard to find because Tigard-Tualatin is already looking at making $4 million in reductions for the next budget year because of inadequate state funding, enrollment drops and inflation, Moore said.

La Grande used ESSER money for around 25 positions, among other things. Some will disappear through attrition, and some will be picked up with Student Success Act and Measure 98 funds. The district is left with an additional $800,000 in staffing costs from ESSER hires, Mendoza said.

All told, the district is facing about $2.25 million in new costs.

“The State School Fund isn’t giving us $2.25 million in new dollars,” he said.

Mendoza said his district is in a strong financial position with reserves and grants but it is facing a sparse future unless the state increases funding.

“We can weather the storm for up to two years,” he said. “But if we don’t have a State School Fund that increases, not only will La Grande be in trouble, there will be many districts in trouble.”

La Grande Board Chair Randy Shaw said his district is “right-sized” for now but he’s worried about the years ahead.

“We’re hoping the state is actually paying attention to what is going on,” Shaw said.

– Jake Arnold, OSBA

[email protected]